I spent the second day outside the city, to the southwest. My primary destination and first stop for the day was Hōryū-ji, a temple founded in 607.

Hōryū-ji was built at the command of the imperial regent, Prince Shōtoku, who was instrumental in the spread of Buddhism in Japan. Prince Shōtoku also ordered the adoption of the Chinese calendar and carried out significant governmental reforms. But while he actively sought out and implemented the best aspects of Chinese culture, he also asserted Japan as being equal to China, putting an end to the previous subordinate relationship. (He famously addressed a letter, “From the Son of Heaven in the Land of the Rising Sun to the Son of Heaven in the Land of the Setting Sun.” The Chinese emperor was not pleased.)

A fire is said to have leveled Hōryū-ji in 670, but even so, the complex contains the longest-standing wooden buildings in the world. And while they’re around a century younger than the temple itself, the gate guardians are the oldest in Japan.

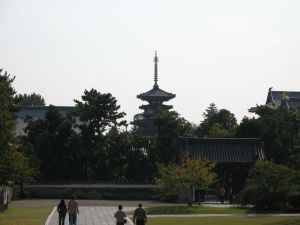

From Hōryū-ji, I moved on to Yakushi-ji, a temple located just within Nara’s city limits, which is still a mile or two outside of the city proper.

Yakushi-ji was established in 680 and moved to its present location in 718. Over the years, nearly all of its buildings have burned down and been rebuilt. The eastern pagoda, built in 730, is the sole remaining original construction.

This round hall, meanwhile, is a totally new addition.

It was built in 1991 to hold a portion of the cremated remains of the famous 7th century Chinese monk, Xuanzang (Jp: Genjō Sanzō). Another portion exists in a museum in India. That one was a gift from the Chinese government, but the remains at Yakushi-ji were taken by Japanese soldiers during World War II.

I wonder how much that bothers China. On the one hand, the Party holds religion in contempt, but on the other hand, Journey to the West, the novel loosely based on Xuanzang’s travels, is a beloved classic. I guess it’s likely that most people simply don’t know about the remains being kept in Japan. I certainly had no idea.

After poking around Yakushi-ji, I had lunch at a small restaurant called Shūraku Ichihashi.

I can’t remember exactly what I had, but I do remember being struck by how low the price was for such good food. I’ve had better meals and I’ve had cheaper meals, but their ¥1,000 (~$10) lunch set was an outstanding bargain for the quality.

Here’s a map. I should note that their dinner prices seemed much higher, so the restaurant is probably best for lunch.

After my somewhat late lunch, my last stop before heading home to Kobe was at Tōshōdai-ji, a short walk north of Yakushi-ji. The main hall was completely walled off due to repair work, but this is the grave of Ganjin, the Chinese monk who founded the temple in 759.

Ganjin (Ch: Jianzhen) was invited to come to Japan to share his knowledge of Buddhism. It took him six tries over the course of a dozen years before he finally made it across the ocean, and he had gone completely blind in the meantime. When Ganjin at last made it to the capital, Nara, he served for five years as the abbot of Tōdai-ji (the temple with the giant statue of Buddha), before retiring to a plot of land granted by the emperor. Ganjin then used the land to build Tōshōdai-ji. He died four years later.

There’s a beautiful mossy grove between the grave and the rest of the temple.

Even disregarding their cultural and historical value, Japan’s many temples and shrines are priceless just for all the green space they protect from encroaching concrete.

Not that there’s no countryside left in Japan. The walk to the nearest train station was quite nice.

It was harvest time in the rice fields.

Houses pressed in at points…

…but then I came upon a particularly novel bit of protected greenery.

This island is a giant, key-shaped burial mound. Scores of these were built as tombs for nobility from the 3rd century to the early 7th century.

This one is officially designated as the tomb of Emperor Suinin, but I don’t know if there’s any evidence supporting that claim. Japan’s Imperial Household Agency lists some 740 burial mounds as being imperial tombs, but excavations are forbidden and it’s widely thought that most of the designations – made in the 19th century – are spurious. A few actually are supported by historical and archeological evidence though, so they aren’t all made up.

In any case, the mound is a literal island of greenery, and a sacrosanct one at that. So rather than being all for the sake of one dead man, the enormous labor that must have been expended to build the tomb ended up producing something that will benefit a great many people for a long, long time.